The composer at Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin, in 2008 | |

| Born | 11 September 1935 (age 83) |

|---|---|

| Nationality | Estonian |

| Alma mater | Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre |

| Occupation | Composer |

Works | List of compositions |

| Spouse(s) | Nora Pärt |

| Awards | |

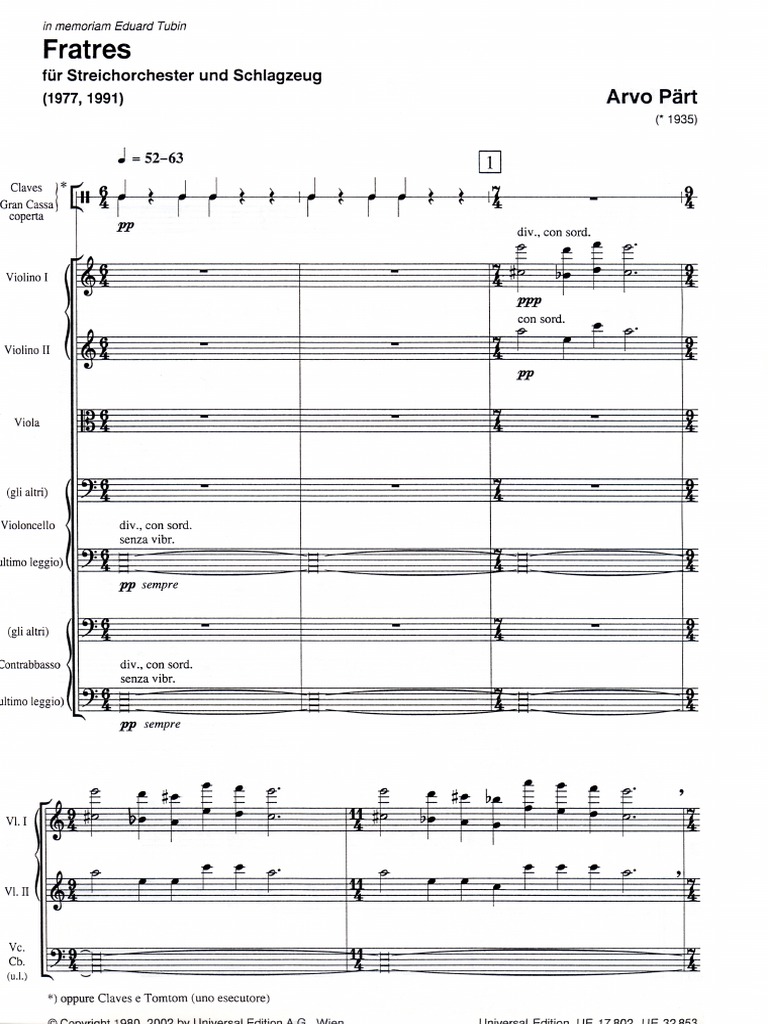

The cello part is actually made from the piano part, but it is good for playing. To download PDF, click the 'Download PDF' button below the appropriate sheet music image. To view the first page of Arvo Part - Fratres for cello and piano (1980) click the music sheet image. PDF format sheet music: Instrument part: 5 pages. 1633 K Piano part: 11. Arvo Part - Fratres for cello and piano (1980). You can download the PDF sheet music Arvo Part - Fratres for cello and piano (1980) on this page. Fratres by Arvo.

Arvo Pärt (Estonian pronunciation: [ˈɑrvo ˈpært]; born 11 September 1935) is an Estonian composer of classical and religious music. Since the late 1970s, Pärt has worked in a minimalist style that employs his self-invented compositional technique, tintinnabuli. Pärt's music is in part inspired by Gregorian chant. His most performed works include Fratres (1977), Spiegel im Spiegel (1978), and Für Alina (1976). Since 2011 Pärt has been the most performed living composer in the world.

- 2Musical development

- 6References

Life[edit]

Pärt was born in Paide, Järva County, Estonia and was raised by his mother and stepfather in Rakvere in northern Estonia.[1] He began to experiment with the top and bottom notes of the family's piano as the middle register was damaged.[2] Pärt's musical education began at the age of seven when he began attending music school in Rakvere. By the time he reached his early teenage years, Pärt was writing his own compositions. His first serious study came in 1954 at the Tallinn Music Middle School, but less than a year later he temporarily abandoned it to fulfill military service, playing oboe and percussion in the army band.[3] After his service he attended the Tallinn Conservatory, where he studied composition with Heino Eller[4] and it was said of him, 'he just seemed to shake his sleeves and the notes would fall out'.[5] As a student, he produced music for film and the stage. During the 1950s, he also completed his first vocal composition, the cantataMeie aed ('Our Garden') for children's choir and orchestra. He graduated in 1963. From 1957 to 1967, he worked as a sound producer for the Estonian public radio broadcaster Eesti Rahvusringhääling.

Pärt was criticized by Tikhon Khrennikov in 1962, for employing serialism in Nekrolog (1960), the first 12-tone music written in Estonia,[6] which exhibited his 'susceptibility to foreign influences'. But nine months later he won First Prize in a competition of 1,200 works, awarded by the all-Union Society of Composers, indicating the inability of the Soviet regime to agree consistently on what was permissible.[7] In the 1970s, Pärt studied medieval and Renaissance music instead of focusing on his own composition. About this same time, he converted from Lutheranism to Orthodox Christianity.[8]

In 1980, after a prolonged struggle with Soviet officials, he was allowed to emigrate with his wife and their two sons. He lived first in Vienna, where he took Austrian citizenship and then relocated to Berlin, Germany, in 1981. He returned to Estonia around the turn of the 21st century and for a while lived alternately in Berlin[9] and Tallinn.[4] He currently resides in Laulasmaa, about 35 kilometres (22 mi) from Tallinn.[10] He speaks fluent German and has German citizenship as a result of living in Germany since 1981.[11][12][13]

In 2014 The Daily Telegraph described Pärt as possibly 'the world's greatest living composer' and 'by a long way, Estonia's most celebrated export'. But when asked how Estonian he felt his music to be, Pärt replied: 'I don’t know what is Estonian... I don’t think about these things.' Unlike many of his fellow Estonian composers, Pärt never found inspiration in the country's epic poem, Kalevipoeg, even in his early works. Pärt said 'My Kalevipoeg is Jesus Christ.'[6]

Musical development[edit]

Familiar works by Pärt are Cantus in Memoriam Benjamin Britten for string orchestra and bell (1977) and the string quintetFratres I (1977, revised 1983), which he transcribed for string orchestra and percussion, the solo violin 'Fratres II' and the cello ensemble 'Fratres III' (both 1980).

Pärt is often identified with the school of minimalism and, more specifically, that of mystic minimalism or holy minimalism.[14] He is considered a pioneer of the latter style, along with contemporaries Henryk Górecki and John Tavener.[15] Although his fame initially rested on instrumental works such as Tabula Rasa and Spiegel im Spiegel, his choral works have also come to be widely appreciated.

In this period of Estonian history, Pärt was unable to encounter many musical influences from outside the Soviet Union except for a few illegal tapes and scores. Although Estonia had been an independent state at the time of Pärt's birth, the Soviet Union occupied it in 1940 as a result of the Soviet–NaziMolotov–Ribbentrop Pact; and the country would then remain under Soviet domination—except for the three-year period of German wartime occupation—for the next 51 years.

Compositions[edit]

Pärt's works are generally divided into two periods. He composed his early works using a range of neo-classical styles influenced by Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and Bartók. He then began to compose using Schoenberg'stwelve-tone technique and serialism. This, however, not only earned the ire of the Soviet establishment but also proved to be a creative dead-end. When early works were banned by Soviet censors, Pärt entered the first of several periods of contemplative silence, during which he studied choral music from the 14th to 16th centuries.[4] In this context, Pärt's biographer, Paul Hillier, observed that 'he had reached a position of complete despair in which the composition of music appeared to be the most futile of gestures, and he lacked the musical faith and willpower to write even a single note.'[16]

The spirit of early European Polyphony informed the composition of Pärt's transitional Third Symphony (1971); thereafter he immersed himself in early music, reinvestigating the roots of Western music. He studied plainsong, Gregorian chant and the emergence of polyphony in the European Renaissance.

The music that began to emerge after this period was radically different. This period of new compositions included the 1977 works Fratres, Cantus in Memoriam Benjamin Britten and Tabula Rasa.[4] Pärt describes the music of this period as tintinnabuli—like the ringing of bells. Spiegel im Spiegel (1978) is a well-known example which has been used in many films. The music is characterised by simple harmonies, often single unadorned notes, or triads, which form the basis of Western harmony. These are reminiscent of ringing bells. Tintinnabuli works are rhythmically simple and do not change tempo. Another characteristic of Pärt's later works is that they are frequently settings for sacred texts, although he mostly chooses Latin or the Church Slavonic language used in Orthodox liturgy instead of his native Estonian language. Large-scale works inspired by religious texts include St. John Passion, Te Deum, and Litany. Choral works from this period include Magnificat and The Beatitudes.[4]

Pärt has been the most performed living composer in the world for seven consecutive years.[17] Of Pärt's popularity, Steve Reich has written: 'Even in Estonia, Arvo was getting the same feeling that we were all getting ... I love his music, and I love the fact that he is such a brave, talented man ... He's completely out of step with the zeitgeist and yet he's enormously popular, which is so inspiring. His music fulfills a deep human need that has nothing to do with fashion.'[18] Pärt's music came to public attention in the West largely thanks to Manfred Eicher who recorded several of Pärt's compositions for ECM Records starting in 1984. Pärt wrote Cecilia, vergine romana on an Italian text about life and martyrdom of Saint Cecilia, the patron saint of music, for choir and orchestra on a commission for the Great Jubilee in Rome, where it was performed, close to her feast day on 22 November, by the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia conducted by Myung-whun Chung.

Invited by Walter Fink, Pärt was the 15th composer featured in the annual Komponistenporträt of the Rheingau Musik Festival in 2005 in four concerts. Chamber music included Für Alina for piano, played by himself, Spiegel im Spiegel and Psalom for string quartet. The chamber orchestra of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra played his Trisagion, Fratres and Cantus along with works of J.S. Bach. The Windsbach Boys Choir and soloists Sibylla Rubens, Ingeborg Danz, Markus Schäfer and Klaus Mertens performed Magnificat and Collage über B-A-C-H together with two Bach cantatas and one by Mendelssohn. The Hilliard Ensemble, organist Christopher Bowers-Broadbent, the Rostock Motet Choir and the Hilliard instrumental ensemble, conducted by Markus Johannes Langer [de], performed a program of Pärt's organ music and works for voices (some a cappella), including Pari intervallo, De profundis, and Miserere.

A new composition, Für Lennart, written for the memory of the Estonian President, Lennart Meri, was played at Meri's funeral service on 2 April 2006.

In response to the murder of the Russian investigative journalistAnna Politkovskaya in Moscow on 7 October 2006, Pärt declared that all of his works performed in 2006 and 2007 would be in honour of her death, issuing the following statement: 'Anna Politkovskaya staked her entire talent, energy and—in the end—even her life on saving people who had become victims of the abuses prevailing in Russia.'[19]

Pärt was honoured as the featured composer of the 2008 RTÉ Living Music Festival[20] in Dublin, Ireland. He was also commissioned by Louth Contemporary Music Society[21] to compose a new choral work based on 'Saint Patrick's Breastplate', which premiered in 2008 in Louth, Ireland. The new work, The Deer's Cry, is his first Irish commission, and received its debut in Drogheda and Dundalk in February 2008.[22]

Pärt's 2008 Fourth Symphony is named Los Angeles and was dedicated to Mikhail Khodorkovsky. It was Pärt's first symphony written since his Third Symphony of 1971. It premiered in Los Angeles, California, at the Walt Disney Concert Hall on 10 January 2009,[23] and was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Classical Contemporary Composition in 2010.[24]

Arvo Part Fratres Cello Pdf

On 10 December 2011, Pärt was appointed a member of the Pontifical Council for Culture for a five-year renewable term by Pope Benedict XVI.[25]

On 26 January 2014, Tõnu Kaljuste, conducting the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, the Sinfonietta Riga, the Tallinn Chamber Orchestra, the Latvian Radio Choir and the Vox Clamantis ensemble, won a Grammy for Best Choral Performance for a performance of Pärt's Adam's Lament.[26]

Fratres Meaning

International centre[edit]

The Arvo Pärt Centre is located in the Estonian village of Laulasmaa, a coastal village located some 35 kilometres (22 mi) west of Tallinn. The centre is responsible for maintaining the composer's archive. In August 2018 Estonian Minister of CultureIndrek Saar invited representatives of the Ministries of Culture of eight countries to participate in the inauguration ceremony of the new centre.[27]

A new building of the centre, which opened to visitors on 17 October 2018, includes in addition to the archives a library, a museum, research facilities, an education centre, and a concert hall.[28][29]

Awards[edit]

- 1996 – American Academy of Arts and Letters Department of Music[30]

- 1996 – Honorary Doctor of Music, University of Sydney[31]

- 1998 – Honorary Doctor of Arts, University of Tartu[32]

- 2003 – Honorary Doctor of Music, Durham University[33]

- 2006 – Order of the National Coat of Arms 1st Class[34]

- 2007 – Brückepreis[35]

- 2008 – Léonie Sonning Music Prize, Denmark

- 2008 – Austrian Cross of Honour for Science and Art, First Class[36]

- 2009 – Foreign Member, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts

- 2010 – Honorary Doctor of Music, University of St Andrews[37]

- 2011 – Chevalier (Knight) of Légion d'honneur, France[38]

- 2011 – Membership of the Pontifical Council for Culture[39]

- 2013 – Archon of the Ecumenical Patriarchate[40]

- 2014 – Recipient of the Praemium Imperiale award, Japan[41]

- 2014 – Honorary Doctor of Sacred Music, Saint Vladimir's Orthodox Theological Seminary[42]

- 2016 – Honorary Doctor of Music, University of Oxford[43]

- 2017 – Ratzinger Prize, Germany[44]

- 2018 – Gold Medal for Merit to Culture – Gloria Artis, Poland[45]

- 2018 – Honorary Doctor of Music, Fryderyk Chopin University of Music[46]

- 2019 – Cross of Recognition, 2nd Class[47]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^'Sounds emanating love – the story of Arvo Pärt'. 11 September 2015. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^Arvo Pärt, Sinfini Music website

- ^'Arvo Pärt – Biography & History'. AllMusic. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- ^ abcdeNew York City Ballet program notes in Playbill, January 2008.

- ^P. Hillier, Arvo Pärt, 1997, p. 27.

- ^ abAllison, John (12 December 2014). 'Arvo Pärt interview: 'music says what I need to say''. The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^Misiunas, Romuald J.; Rein, Taagepera (1983). The Baltic States, Years of Dependence, 1940–1980. University of California Press. p. 170. ISBN0-520-04625-0.

- ^Peter Quinn. Arvo Pärt, BBC Music Magazine, the official website of BBC Music Magazine

- ^'Radio :: SWR2 – SWR.de'(PDF). swr.online. Archived from the original(PDF) on 23 August 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^Clements, Andrew (19 April 2018). 'Arvo Pärt: The Symphonies review – the Parts that make the whole'. The Guardian. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- ^P. Hillier, Arvo Pärt, 1997, p. 33.

- ^'Arvo Pärt Special 1: How Sacred Music Scooped an Interview'. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^P. Bohlman, The Music of European Nationalism: Cultural Identity and Modern History, p. 75.

- ^For example, in an essay by Christopher Norris called 'Post-modernism: a guide for the perplexed,' found in Gary K. Browning, Abigail Halcli, Frank Webster, Understanding Contemporary Society: Theories of the Present, 2000.

- ^Thomas, Adrian (1997). Górecki. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 135. ISBN0-19-816393-2.

- ^P. Hillier, Arvo Pärt, 1997, p. 64.

- ^'7th year running: Arvo Pärt is the world's most performed contemporary composer'. universaledition.com. 10 January 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^Hodgkinson, Will. 'The Reich stuff'. The Guardian, 2 January 2004. Retrieved, 18 February 2011.

- ^'Arvo Pärt commemorates Politkovskaja'(PDF). Universal Edition Newsletter. Universal Edition (Winter 2006/2007): 13. 2007. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^'Arvo Pärt describes RTÉ Living Music Festival as 'best festival of my life'' (Press release). Raidió Teilifís Éireann.

- ^'Baltic Voices in Ireland: Arvo Pärt's World Premiere – Louth Contemporary Music Society'. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^http://www.artmedia.ee, Art Media Agency OÜ. 'Music News – Estonian Music Information Centre'. emic.ee. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^In Detail: Arvo Pärt's Symphony No. 4 'Los Angeles'. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- ^'Arvo Part'. 22 May 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^NOMINA DI MEMBRI DEL PONTIFICIO CONSIGLIO DELLA CULTURAArchived 7 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^Arvo Pärt’s “Adam’s Lament” wins Grammy Award in the Best Choral Performance category!. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ERR (7 August 2018). 'Minister invites foreign representatives to opening of Arvo Pärt Centre'. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^'Arvo Pärt Centre'. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^'About the Centre – Arvo Pärt Centre'. www.arvopart.ee. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^'Arvo Pärt – Estonian composer'. britannica.com. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^'Honorary Awards: University of Sydney'. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ^Shenton, Andrew (17 May 2012). 'The Cambridge Companion to Arvo Pärt'. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 15 October 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^'Arvo Pärt: Doctor of Music'(PDF). 15 October 2003. Archived from the original(PDF) on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2008.

- ^'President Arnold Rüütel jagab heldelt üliharuldast ordenit'. Postimees. 12 January 2006. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^'Internationaler Brückepreis geht an: / 2007 – Arvo Pärt / Estnischer Komponist' [International Brückepreis goes to: / 2007 – Arvo Pärt/ Estonian composer] (in German). 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^'DiePresse.com'. 9 May 2008. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^'Honorary Degrees June 2009'. 17 June 2009. Archived from the original on 24 June 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^'Le compositeur Arvo Pärt décoré de l'ordre de la Légion d'Honneur'. ambafrance-ee.org. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^'Vatican information service'. 12 December 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- ^'Arvo Pärt Receives Distinction from Patriarch Bartholomew'. 9 September 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ^'Arvo Pärt, Athol Fugard among recipients of Praemium Imperiale awards'. Los Angeles Times. 16 July 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- ^'Honorary Degrees May 2014'(PDF). svots.edu. 31 May 2014. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^'Oxford announces honorary degrees for 2016'. ox.ac.uk. 25 February 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^'An Orthodox, a Lutheran, and a Catholic win the 2017 Ratzinger Prize'. 26 September 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- ^Łozińska, Olga (26 November 2018). 'Kompozytor Arvo Part uhonorowany Złotym Medalem Zasłużony Kulturze Gloria Artis'. dzieje.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^'Two eminent prizes to Arvo Pärt from Poland'. 25 November 2018. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^'Estonian composer Arvo Part decorated with Latvia's Cross of Recognition, 2nd Class'. The Baltic Course. 11 March 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

Sources[edit]

- Works cited

- Hillier, Paul. (1997). Arvo Pärt. Oxford : Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-19-816616-0 (paper)

Further reading[edit]

- Chikinda, Michael (2011). 'Pärt's Evolving Tintinnabuli Style'. Perspectives of New Music 49, no. 1 (Winter): pp. 182–206

- Arvo Pärt, Enzo Restagno, Leopold Brauneiss and Saala Kareda (2012). Arvo Pärt in Conversation, translated from the German by Robert Crow. Estonian Literature Series. Champaign, IL: Dalkey Archive PressISBN9781564787866

- Shenton, Andrew (ed.) (2012). The Cambridge Companion to Arvo Pärt. Cambridge: Cambridge University PressISBN9780511842566

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Arvo Pärt |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arvo Pärt. |

Arvo Part Fratres Cello Quartet

- Arvo Pärt biography and works on the UE website (publisher)

- Arvo Pärt – extensive site

- Biography in MUSICMATCH Guide – small biography and list of works.

- Arvo Pärt and the New Simplicity – article by Bill McGlaughlin, with audio selections

- Lancing College Commission Original Claudio Records Recording in the presence of the composer – Review/Information (dead link)

- Arvo Pärt Centre – most up-to-date info and more

- Arvo Pärt on IMDb