- Metamorphoses (Penguin Classics) by Ovid,Mary M. Innes and a great selection of related books, art and collectibles available now at AbeBooks.com. Ovid Mary M Innes - AbeBooks abebooks.com Passion for books.

- Right after the publication of the Metamorphoses (while it was itself still changing, in fact, constantly being revised by its fretting author), a horrible transformation came upon Ovid himself: he was banished from Rome, sent into exile at Tomis on the edge of the Roman world (I’ve written about it here). He begged to be returned (or at.

Metamorphoses (Penguin Classics) by Ovid,Mary M. Innes and a great selection of related books, art and collectibles available now at AbeBooks.com. Ovid Mary M Innes - AbeBooks abebooks.com Passion for books.

| Metamorphoses | |

|---|---|

| Written by | Mary Zimmerman |

| Characters | Myrrha Midas Hermes Phaeton Aphrodite Erysichthon Alcyone King Ceyx Orpheus Eurydice Therapist Apollo Baucis Philemon Ceres Psyche Eros |

| Date premiered | 1996 |

| Place premiered | Northwestern University Chicago, Illinois |

| Original language | English |

| Genre | Drama, comedy |

Metamorphoses is a play by the American playwright and director Mary Zimmerman, adapted from the classicOvid poem Metamorphoses. The play premiered in 1996 as Six Myths at Northwestern University and later the Lookingglass Theatre Company in Chicago. The play opened off-Broadway in October 2001 at the Second Stage Theatre. It transferred to Broadway on 21 February 2002 at the Circle in the Square Theatre. That year it won several Tony Awards.

It was revived at the Lookingglass Theatre Company in Chicago on 19 September 2012 and was produced in Washington, DC at the Arena Stage in 2013.[1]

Background[edit]

Mary Zimmerman's Metamorphoses is based on David R. Slavitt's free-verse translation of The Metamorphoses of Ovid. She directed an early version of the play, Six Myths, in 1996 at the Northwestern University Theater and Interpretation Center. Zimmerman's finished work, Metamorphoses, was produced in 1998.

Of the many stories told in Zimmerman's Metamorphoses, only the introductory 'Cosmogony' and the tale of Phaeton are from the first half of Ovid's Metamorphoses. The story of Eros and Psyche is not a part of Ovid's Metamorphoses; it is from Lucius Apuleius' novel Metamorphoses[2] —also called The Golden Ass—and was included in Zimmerman's Metamorphoses because, as Zimmerman said in an interview with Bill Moyers of PBS NOW, 'I love it so much I just had to put it in.'[3]

She wrote and directed Metamorphoses during a period of renewed interest in the life and writings of Ovid.

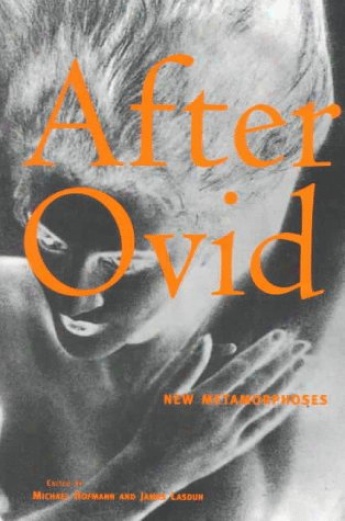

Other Ovid-related works published in the same decades include David Malouf's 1978 novel, An Imaginary Life; Christoph Ransmayr's Die letzte Welt (1988) (The Last World, translated into English by John E. Woods in 1990); and Jane Alison's The Love-Artist (2001). Additionally, Ovid's Metamorphoses were translated by A.D. Melville, Allen Mandelbaum, David R. Slavitt, David Michael Hoffman and James Lasdun, and Ted Hughes—in 1986, 1993, 1994, 1994, and 1997, respectively.[2]:623

Plot synopsis[edit]

The play is staged as a series of vignettes. The order is as follows:

- Cosmogony — Used to explain the creation of the world, as well as give the audience a sense of the style and setting of the play. Woman by the Water, Scientist, and Zeus help narrate how our world of order came from chaos, either by the hand of a creator or by a 'natural order of things.'[4]:7

- Midas — The story is framed by the narration of three laundresses, who tell the story of King Midas, a very rich man. After Midas shuns his daughter for being too disruptive during his speech about caring for his family, a drunken Silenus enters and speaks of a distant land capable of granting eternal life. Silenus later falls asleep, and Midas shelters him in the cabana. When Bacchus comes to retrieve Silenus, he grants Midas a wish for his gracious care of Silenus. Midas asks to have whatever he touches turn to gold. Midas accidentally turns his beloved daughter into gold and is told by Bacchus to seek a mystic pool, which will restore him to normal. Midas leaves on his quest.

- Alcyone and Ceyx — Also narrated by the three laundresses, this story portrays King Ceyx and his wife Alcyone. Despite his wife's warnings and disapproval, Ceyx voyages on the ocean to visit a far off oracle. Poseidon, the sea god, destroys Ceyx's ship and the king dies. Alcyone awaits him on shore. Prompted by Aphrodite, Alcyone has a dream of Ceyx, who tells her to go to the shore. With mercy from the gods, the two are reunited. Transformed into seabirds, they fly together toward the horizon.

- Erysichthon and Ceres — This story tells of Erysichthon, man of no god, who chops down one of Ceres' sacred trees. For vengeance, Ceres commands the spirit Hunger to make Erysichthon captive to an insatiable appetite. After eating endlessly and spending all his gold on food, Erysichthon tries to sell his mother to a merchant. His mother is transformed into a little girl after praying to Poseidon and escapes. Erysichthon eventually falls to his endless hunger and devours himself.

- Orpheus and Eurydice — The story of Orpheus, the god of music, and Eurydice is told from two points of view., the first is from the point of view of Orpheus in the style of Ovid from 8 AD, who has just married his bride Eurydice. Bitten by a snake on their wedding day, Eurydice dies. Distraught, Orpheus travels to the Underworld to negotiate with Hades and the gods to free Eurydice. After Orpheus sings a depressing song, Hades, the god of the Underworld, agrees to let Eurydice return with Orpheus as long as Eurydice follows Orpheus from behind, and he does not look back at her. If he does, she must stay in the Underworld. Orpheus agrees but, when almost back to the living world, he looks back, as he could not hear Eurydice, causing Hermes to return her to Hades. The action is repeated several times, resembling the memory that Orpheus will have forever of losing his bride. The second time is told from the point of view of Eurydice, in the style of the poet Rainer Maria Rilke from 1908. After an eternity of this repeated action, Eurydice becomes forgetful and fragile, no longer remembering Orpheus. She returns to the Underworld ignorant of Orpheus, the man she loved so long ago.

- Narcissus Interlude — A brief scene showing Narcissus catching a glimpse of his own reflection in a pool. Enthralled, he becomes frozen. The actors replace him with a narcissus plant.

- Pomona and Vertumnus — A female wood nymph, Pomona, becomes involved with the shy Vertumnus. Pomona has refused the hands of many suitors and remains alone. Vertumnus, in order to see her, disguises himself in a variety of gimmicks. Trying to convince Pomona to fall in love with him, he refuses to show himself. After telling the story of Myrrha, Pomona tells Vertumnus to take off his ridiculous disguise, and the two fall in love.

- Myrrha — Vertumnus tells the story of King Cinyras and his daughter Myrrha. After denying Aphrodite's attempts many times to turn her head in love, Myrrha is cursed by Aphrodite with a lust for her father. Myrrha tries to control her urges, but eventually falls to temptation. With the help of her Nursemaid, Myrrha has three sexual encounters with her father, each time keeping him inebriated and blind so he would not know it's her. The third time Cinyras takes off his blindfold and tries to strangle Myrrha, who escapes and is never seen again.

- Phaeton — Phaeton narrates his relationship with his father, Apollo (the sun god), to the Therapist. With the Therapist adding her psychoanalytical points, Phaeton tells the audience of a distanced relationship with his father. After bullying at school, Phaeton goes on a journey to meet his father, who drives the sun across the sky every day. Racked with guilt from neglect of his son, Apollo allows Phaeton to 'drive' the sun across the sky as compensation for his years of absence. Phaeton, who constantly whines, drives the sun too close to the earth and scorches it. The Therapist closes the scene in a monologue about the difference between myth and dream.

- Eros and Psyche — 'Q' and 'A' essentially narrate a scene about Psyche falling in love with Eros. Psyche and Eros remain silent during the whole interlude, but act out what Q and A discuss. Eros and Psyche fall in love, as Q and A tell the audience that they might wander in the darkness of loneliness until they blind themselves to personal romantic desires and give in to a deeper love. Psyche becomes a goddess and lives with Eros forever.

- Baucis and Philemon — The final story tells of Zeus and Hermes disguising themselves as beggars on earth to see which people are following the laws of Xenia. After being shunned by every house in the city, they are accepted into the house of Baucis and Philemon, a poor married couple. The couple feed the gods with a great feast, not knowing the identity of the strangers, except that they are 'children of God'.[4]:79 After the feast, the gods reveal themselves and grant the two a wish. Baucis and Philemon ask to die at the same time to save each other the grief of death. The gods transform their house into a grand palace and the couple into a pair of trees with branches intertwined. At the end of the scene, Midas returns to the stage, finds the pool, washes, and is restored. His daughter enters, restored from being fixed as a gold piece, and the play ends with a redeemed Midas embracing his daughter.

The stories as they are told in the classic Ovid tales:

- Characters

- Alcyone and Ceyx

- Orpheus and Eurydice

- Pomona and Vertumnus

Plot analysis[edit]

David Rush notes that in this case, the plot is the playwright's deliberate selection and arrangement of the incidents and actions.[5] When Metamorphoses is not a conventional arrangement and has a non-linear point of view.[5]:37

A linear dramatic action may be set as with the following steps:

- A state of equilibrium

- An inciting incident

- Point of attack of the major dramatic question

- Rising action

- Climax

- Resolution

- New state of equilibrium.[5]:38–39

These set of events are described as being of a well-made play and follow a linear set of actions.[5]:37 First one event, then the next and the following one after that and so on and so forth. Metamorphoses does not follow this laid out set of steps and no single analysis can make it follow this formula. However each of the separate stories embedded within the play is in itself a 'well-made play' within a play. Each story can be easily followed and analyzed through a look at the seven parts already established. An example that can easily demonstrate and lay out the structure is the story of Erysichthon described within Metamorphoses.

The seven elements of this story can be seen as follows:

- State of Equilibrium — Erysichthon has no regard for the gods and does as he wishes with no fear of punishment

- Inciting Incident — Erysichthon tears down a tree that is beloved by the god, Ceres

- Point of Attack of the MDQ (Major Dramatic Question) — Will Ceres avenge her beloved tree and teach a valuable lesson about the power of the gods to Erysichthon?

- Rising Action — Ceres sends a servant to look for Hunger, Ceres' servant finds Hunger, Hunger embodies itself into Erysichthon, Erysichthon gorges on food

- Climax — Erysichthon's hunger is so insatiable that he sells his own mother to a trader for money to buy more food

- Resolution — Finally, Erysichthon can no longer find any more food to eat and curb his hunger so Ceres approaches him with a tray that holds a fork and a knife, Erysichthon sits down and actually destroys himself

- New State of Equilibrium — Erysichthon is no more and people are no longer left to wonder or question the power of the gods

Each of the stories told within Metamorphoses can be analyzed in this fashion and it is even worth noting the story of King Midas. His dramatic action can be followed over the entire length of the play for we are introduced to his story in the beginning and are not subjected to the resolution of his story until the end of the play and his story is actually the last one addressed in the play.[5]:35–39

Character guide[edit]

(as listed in the script)

- Woman by the Water: The narrator for the opening scene who comments on the creation of the world and man.

- Scientist: In the opening scene, explains the scientific possibility of the creation of the world

- Zeus: The Greek God, referred in the play as, 'Lord of the heavens', who represents a divine creator in the opening scene. In the penultimate scene, Zeus and Hermes disguise themselves as beggars.

- Three Laundresses: The three unnamed women tell the stories of 'Midas' and 'Alcyone and Ceyx,' as they are enacted on stage.

- Midas and his Daughter: A rich king, Midas is greedy for more gold.

- Lucina: The goddess of childbirth.

- Eurydice: Wife of Orpheus who dies after stepping on a snake. She is eventually doomed to the Underworld after Orpheus breaks his promise to Hades, and will spend as eternity not remembering the face of her husband.

- Silenus: A follower of Bacchus who shows up drunk at Midas' palace. Midas treats Silenus well, and because of his kindness is granted a wish of his choice.

- Bacchus:Roman God of wine and partying. He grants Midas a gift for saving a follower of his, the golden touch, though he warns Midas it is a very bad idea for a heavenly gift.

- Ceyx, a King: King, husband of Alcyone, and captain of a sea vessel. Dies at sea by Poseidon's wrath. His body is later carried ashore by Hermes, and transforms into a living seabird along with Alcyone.

- Alcyone: Ceyx's wife and daughter of Aeolus, Master of the Winds. Awaits for Ceyx's return after his departure, sees false visions of Ceyx as prompted by Morpheus, and finally is transformed into a seabird after Ceyx's body is finally returned to her.

- Hermes: Son of Zeus. Returns Ceyx's body to Alcyone. Later accompanies Zeus to earth disguised as beggars to 'see what people were really like.'[4]:77

- Aphrodite: Goddess of love and beauty. Hears the prayers of Ceyx at sea when his ship is sinking. Sends Iris, the rainbow, to the cave of Sleep, who will show Alcyone a vision of Ceyx.

- Erysichthon and his Mother: Erysichthon scorned the gods and found nothing sacred. Was cursed by Ceres with an insatiable hunger after cutting down a sacred tree. Erysichthon tries to sell his mother, who later turns back into a child by Poseidon's grace. Erysichthon eventually eats himself, though the audience doesn't see it firsthand.

- Ceres: Roman Goddess of the Harvest. Roman equivalent to Demeter. She sends Oread to find Hunger so she can punish Erysichthon for cutting down her tree.

- Oread: A nymph Ceres sends to find Hunger.

- Hunger: Commanded, or rather permitted, to latch onto Erysichthon forever.

- Orpheus: Husband of Eurydice. Travels to the Underworld to retrieve Eurydice after her death. Hades agrees to her release on the condition that Orpheus doesn't look back at her as they walk out of the Underworld; which Orpheus does. He is haunted with the memory of losing his wife forever.

- Vertumnus, God of Springtime: An admirer of Pomona and disguises himself in various costumes in order to get close of Pomona. Tells the story of Myrrha to sway Pomona into loving him.

- Pomona, Wood Nymph: A skilled gardener who refused to have a lover. Finally falls for Vertumnus after heeding his message and telling him to be himself.

- Cinyras, a King: Father to Myrrha who eventually sleeps with her after being tricked by the Nursemaid while being drunk and blindfolded.

- Myrrha: Daughter of King Cinyras who denied Aphrodite so many times that Myrrha was seized with a passion for her father. She eventually has three sexual encounters with her father, the third of which he discovers her identity during intercourse. She flees and her final whereabouts remain unknown.

- Nursemaid: A servant who agrees to help Myrrha have sexual relations with her father.

- Phaeton: Son of Apollo, who after many years of neglect, finally confronts his father, convinces Apollo to let him have control of the sun, and burns the Earth. Phaeton reveals his story to the Therapist.

- Therapist: A psychologist who follows a Freudian example and psycho analyzes Phaeton's story.

- Apollo: God of the sun, music, and light. Father of Phaeton. At first he was hesitant to let his son drive his chariot but eventually gave in.

- Eros: Primordial god of love and lust. Depicted as blind, winged, and naked. Falls in love with Psyche.

- Psyche: The opposite character of Eros. Questions love's reason and eventually receives love. Goddess of pure beauty.

- Q & A: Narrators of the Eros and Psyche scene. Q only asks questions and A answers them. They discuss the relationship of love and the mind.

- Baucis: A poor woman and wife of Philemon. Together they offer their homes to Zeus and Hermes and are rewarded by being turned into trees to spare each other death.

- Philemon: A poor man and husband of Baucis. Together they offer their homes to Zeus and Hermes and are rewarded by being turned into trees to spare each other death.

- Various Narrators: Members of the ensemble who take turns in narrating various scenes.

Character analysis[edit]

Because of the mythic quality of the script, sometimes the players in the performance often resemble 'archetypes instead of characters.'[6] Miriam Chirico describes the work as 'enacting myth does not require creating a plausible character, but rather an emblematic figure who demonstrates a particular, identifiable human trait.'[7]

The story of Orpheus and Eurydice is told twice, each to emphasize their individual stories and act like mirrors with reflecting stories of love and loss; the first being from Orpheus' point of view from Ovid's tale from 8 A.D., then Eurydice's tale in 1908 inspired by German poet Rainer Maria Rilke. Orpheus is an archetype for strong human emotion and expressing it through poetry and music. Music is related to Orpheus' ability to move only forward in time, along with his feelings and mortal love. Although they can repeat, as they do in the scene several times, they cannot turn back completely and be the same. Zimmerman includes with the line, 'Is this a story about how time can only move in one direction?' to bring light to Orpheus' struggle.[8]

Phaeton narrates his own story (not the case with most of the other stories). With the Therapist bringing a glimpse of Freudianpsychoanalysis, Phaeton's relationship with his father can be seen in new ways: 'the father is being asked to perform an initiation rite, to introduce his son to society, [and] to inscribe him in a symbolic order.'[8]:75

Because Midas frames the story at the beginning and returns at the end as a redeemed man, the play ends with a sense of optimism due to his transformation.

The character Eros, although he attains many of the traits of the more popularized Cupid, is meant to symbolize more. In the play, 'A', Psyche, interprets why 'Q', Eros, is presented as naked, winged, and blindfolded: he is naked to make our feelings transparent, he is winged so he might fly from person to person, and he is blindfolded to encourage us to see into each other's hearts.[7]:175 A, a narrator of the Eros and Psyche scene, says, 'He is blind to show how he takes away our ordinary vision, our mistaken vision, that depends on the appearance of things.'[4]:69

Genre[edit]

Since the Metamorphoses is derived from literary texts, productions of Zimmerman's may be classified in the genre of Readers Theater.[7]:157–158 According to Miriam Chirico, Readers Theater presents a narrative text to an audience, for instance a poem rather than action that follows a typical play script. Readers Theater generally follows the 'presentational' form of theater, rather than representational, often relying on narrators to bring insight from an outside perspective to a character. The presentational aspect creates a direct link between the audience and the narrator. Readers Theater reduces theatrical devices, such as costumes, sets, and props, to concentrate on the story and the language.[7]:157–158Metamorphoses follows these methods by using multiple narrators, who both tell and comment on the story, and language that is strongly rooted in the David R. Slavitt translation of Ovid.

Compared to classic genres, Metamorphoses is a hybrid containing elements of various genres, including comedy, classic tragedy, and drama, but not necessarily limited to any of them.[8]:73 The play borrows aspects from opera, as it uses visual and aural illusions, and achieves them in simple ways.[8] Joseph Farrell praised Zimmerman for capturing the seriocomic elements of Ovid's tales better than in most adaptations.[2]:624

Style[edit]

Based on myths thousands of years old, Zimmerman's Metamophoses demonstrates their relevance and emotional truths. The play suggests that human beings haven't changed to the point of being unrecognizable nearly two thousand years later. Zimmerman has said, 'These myths have a redemptive power in that they are so ancient. There's a comfort in the familiarity of the human condition.'[7]:165 Zimmerman generally presents an objective point of view. An example is the Alcyone and Ceyx passage, when the audience learns of Ceyx's death long before Alcyone does. In terms of motifs, Metamorphoses is more subjective, especially related to the theme of death and love. The play promotes suggesting death as a transformation of form rather than death as an absence, which is more typical in popular Western culture.[7]:159

A non-naturalistic play, Metamorphoses is presented as mythic rather than realistic.[7]:159 The use of myths essentially 'lifts the individuals out of ordinary time and the present moment, and places him in 'mythic time'—an ambiguous term for the timeless quality myths manifest.'[7]:153 The setting of the play isn't limited to just one specific location. For example, the pool on stage transforms from 'the luxurious swimming pool of nouveau riche Midas, the ocean in which Ceyx drowns, the food devoured by Erysichthon, Narcissus' mirror, a basin to hold Myrrha's tears, [and] the river Styx'[2]:624 and that the pool, like the stories transcend realistic thinking and are 'suspended in space and time.'[9]

The plot is constructed as a series of vignettes, framed overall by a few narrative devices. The opening scene essentially shows the creation of the world, or Cosmogony, not only sets up the world that the following characters will live in, but the world itself. In terms of a beginning and end within the stories themselves, King Midas frames them with his story of greed at the beginning and his redemption at the last moments of the play. After being introduced as a horribly selfish man, the other stories of the play get told and mask the lack of resolution within the Midas story. Finally at the end, Midas who is 'by this time long forgotten and in any case unexpected--reappears, newly from his quest' with his restored daughter, and 'on this note of love rewarded and love redeemed, the play comes to an end.'.[2]:626 Through all the vignettes that are portrayed, the audience is meant to leave not with the story of a few individuals, but rather to know the power of human transformation in all forms.

Metamorphoses uses a combination of presentational and representational forms, including the Vertumnus and Pomona scene, which is both acted out and tells the story of Myrrha. Representation is used as a rendition of a story. For the most part, the play follows a linear technique by having the sequence of events in each individual story follow a rational chronological timeline. The Orpheus scene strays from this, by repeating a portion of the same scene numerous times to emphasize the torment of his loss.

Zimmerman intended the play to build on a foundation of images. In a New York Times interview, Zimmerman said, 'You're building an image, and the image starts to feed you.' She said, 'When I approach a text, I don't do a lot of historical reading. It's an artificial world and I treat it as an artificial world.'[10] Miriam Chirico has described Zimmerman's plays as 'theater of images' and compared to the style of the director Robert Wilson, Pina Bausch, and Julie Taymor.[7]:152 Zimmerman uses the play as a 'poetic bridge between myth and modernism' by creating a hybrid of ancient Greek and modern American cultures.[8]:71

Metamorphoses expresses general concepts and emotions, rather than focusing on individual characters.

Theme/Idea[edit]

The central idea of Metamorphoses is the concept of change. To 'metamorphose' means the striking change in appearance or character of something.[11] Each story contains at least one example.

The theme of change is expressed by the play's use of water. The set includes centrally placed pool, into which characters move and leave as they are transformed. The water is used for different functions throughout Metamorphoses, and it is described as 'the most protean (lit: diverse or varied) of elements'[2]:624 In transforming her early version of Metamorphoses, Six Myths, into its final form, Zimmerman's most significant change was the addition of the central pool. According to David Ostling, Zimmerman's scenic designer, 'She was looking for the changing ability of water, the instantaneous nature of it, how it could go from still to violent and back to calm.'[12]

Zimmerman's play also examines the causes of change in persons. What can make a person become something completely different? The most frequent cause throughout Metamorphoses is love. At the same time, Metamorphoses warns of what happens when love is ignored. When Erysichthon cuts down a sacred tree, showing that he loves only himself, he is transformed into a man consumed by hunger, eventually eating himself. When the beautiful Myrrha scorns the love of her suitors, the goddess Aphrodite curses her to love her father. Discovered, she flees to the wilderness, where the gods transform her into tears.[4]

Ovid The Metamorphoses Pdf

Zimmerman has said that '[Metamorphoses] makes it easy to enter the heart and to believe in greater change as well... that we all can transform.'[3]

Spectacle[edit]

The primary feature of the set in Metamorphoses is the pool, which generally sits center stage and occupies most of the stage. The pool is central to all of the stories, although its function changes. During the production, for instance, it becomes a swimming pool, a washing basin, the River Styx of the Underworld, and the sea.[4] The stage set consists of a platform bordering the pool, a chandelier hanging above, a large depiction of the sky upstage and right of the pool, and a set of double doors, upstage left of the pool. The stage has been described as 'reminiscent of paintings by Magritte and the dream states they evoke.'[12]

The costumes of the play are described as 'evocative of a generalized antiquity but one in which such things as suspenders and trousers are not unknown.'[2]:624 Actors wear costumes that range from classic Grecian togas to modern bathing suits, sometimes in the same scene. This juxtaposition of old and new is particularly striking in the story of Midas, in which he is shown wearing a 'smoking jacket' and confronted by a drunken reveler in a half-toga with vine leaves in his hair.[12]

Language[edit]

The language in Metamorphoses sets up the mythic, yet comprehensible world, to be portrayed on stage. Philip Fisher describes the myths as 'poetic' and says that Zimmerman 'has a great vision and her sense of humor intrudes on a regular basis, often with clever visual or aural touches.'[13] The comedy elements present contemporary connections for the audience to the mythic stories. When an audience hears a clever interjection by Zimmerman, they can easily take in the experience of a well-written play.[13]

Zimmerman's rhythm in the play establishes quick scenes and down-to-the point dialogue, making it easy to follow. She does not leave much silence or pauses. This upbeat rhythm shows up within separate lines as well. For example, 'HERMES: The god of speed and distant messages, a golden crown above his shining eyes, his slender staff held out in front of him, and little wings fluttering at his ankles: and on his left arm, barely touching it: she.'[4]:45 A device known as 'dissonance' is strongly used in this particular line. Dissonance is a subtle sense of disharmony, tension, or imbalance within the words chosen in the play.[5]:86 Dissonance uses short, stressed sounds, as in this example; the playwright uses them to emphasize the up-tempo rhythm throughout the play.

Music[edit]

Willy Schwarz composed the music, for which he was awarded the 2002 Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Music in a Play. Schwarz also collaborated with Zimmerman in her plays The Odyssey and Journey to the West.[14] His music often signifies a change in scene or accompanies specific moments, often one or more of poetic speech.

Finger cymbals are used in the story of Midas, to indicate his footsteps after he has the power of transforming all he touches to gold.[4]:18 During the story of Phaeton, Apollo sings the aria 'Un Aura Amorosa' from Cosí Fan Tutte by Mozart .

Production history[edit]

(Times and dates retrieved from the beginning of the script.[4])

- World premiere production: Lookingglass Theatre Co., Chicago. It opened on October 25, 1998 at the Ivanhoe Theater.

- Second Stage Theatre production: The play's off Broadway debut was on October 9, 2001 in New York City. This production was in rehearsal during the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Towers. With the towers still smoldering downtown and many people suffering losses, the production inspired considerable emotional response from the audiences.[8]:76

- Broadway production: The debut was on March 4, 2002 at the Circle in the Square theater in New York City. Unlike previous productions, the Circle in the Square Theater uses a 3/4 thrust stage, meaning that the audience is on three sides of the playing area. It is related to similar structures of the Greek and Roman amphitheaters. The audience was aware of members on the other sides of the stage, 'appropriate for a show that stresses the value of shared cultural myths and the emotions they summon.'[15] Although the play kept many of the Off-Broadway aspects of the show, it subdued the incest scene between Myrrha and King Cinyras for the Broadway production. The Off Broadway scene had the pair 'writhing and splashing' enthusiastically in a much more intense and disturbing fashion; on Broadway they gently rolled in the water.[8]:78

Margo Jefferson commented that the performance style fell into an American jokiness form; its youthful charm and a high energy was a way to deflect and delay an emotionally heavy scene, but this had more resonance.[16] It closed on February 16, 2003, after a total of 400 performances.[17] This production was nominated for the Tony Award for Best Play in 2002, competing against Suzan-Lori Parks' Topdog/Underdog and Edward Albee's The Goat, or Who is Sylvia?, which took the award.[18]

Despite the staging challenges, with a pool of water for actors to swim and frolic in required to successfully produce the show, the play has been popular on stages throughout the United States. Constellation Theatre Company in Washington, D.C. produced the show in 2012, directed by Allison Arkell Stockman and featuring live music by Tom Teasley.[19]Arena Stage in Washington, D.C. brought the Lookingglass Theatre Company's production, directed by Mary Zimmerman, to its Fichandler Stage in 2013.[20]

About the author[edit]

Ovid Metamorphoses Mary Innes

Mary Zimmerman was born in Lincoln, Nebraska, in 1960. As a child she was introduced to the stories of the ancient Mediterranean world by Edith Hamilton's Mythology. While studying in England, a teacher read her The Odyssey.[3] Zimmerman was educated at Northwestern University, where she received a BS in theater, as well as an MA and PhD in performance studies. She is a full professor of performance studies at Northwestern.[21]

Beyond her childhood fascination with Greek myths, Zimmerman credits the Jungian scholar James Hillman as the source of many of her ideas involving love, such as that in the story of Eros and Psyche. She also acknowledges the influence of Joseph Campbell, a scholar of mythology, in her work.[3] Zimmerman won the MacArthur 'Genius' Fellowship in 1998 in recognition of her creative work.[8]:69

Her plays include Journey to the West, The Odyssey, The Arabian Nights, The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci, and Eleven Rooms of Proust. She also co-wrote and directed Galileo Galilei.[21] She has twice directed for the New York Shakespeare Festival in the Park. In 2002 she won the Tony Award for Best Director for the Broadway production of Metamorphoses.[22]Metamorphoses was Zimmerman's first Broadway production.[2]

Awards and nominations[edit]

- Awards

- 2002 Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Play

- 2002 Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Music in a Play

- 2002 Drama League Award for Best Play

- 2002 Lucille Lortel Award for Outstanding Play

- 2002 Tony Award for Best Direction of a Play (Mary Zimmerman)

- Nominations

- 2002 Tony Award for Best Play

References[edit]

- ^'Metamorphoses'. Looking Glass Theater. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ^ abcdefghFarrell, Joseph (Winter 2002). 'Metamorphoses: A Play by Mary Zimmerman'. The American Journal of Philosophy. 123 (4): 626.

- ^ abcdMoyers, Bill. Interview with Mary Zimmerman. NOW with Bill Moyers. PBS. 22 March 2002

- ^ abcdefghiZimmerman, Mary; Slavitt, David R.; Ovid (2002). Metamorphoses: A Play (First ed.). Evanston: Northwestern University Press. ISBN978-0-8101-1980-2.

- ^ abcdefRush, David (2005). A Student Guide to Play Analysis. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois Printing Press. p. 35.

- ^Brantley, Ben. 'Dreams of Metamorphoses Echo in a Larger Space', New York Times 5 Mar. 2002: Sec. E.

- ^ abcdefghiChirico, Miriam M. (Summer 2008). 'Zimmerman's Metamorphoses: Mythic Revision as a Ritual for Grief,'. Comparative Drama. 42 (2): 153.

- ^ abcdefghGarwood, Deborah (January 2003). 'Myth As Public Dream: The Metamorphosis of Mary Zimmerman's Metamorphoses.'. PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art. 25 (73): 74.

- ^Whitworth, Julia E. Rev. of Metamorphoses by Mary Zimmerman. Theatre Journal Vol. 54 Is. 4 (Dec. 2002): 635.

- ^Marks, Peter. 'Building Her Plays Image by Image,' New York Times 9 March 2002, late ed.: B7.

- ^Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Metamorphose. Merriam-Webster, Inc.

- ^ abcEddy, Michael S. 'Metamorphosing Metamorphoses: scenic designer Daniel Ostling discusses moving Mary Zimmerman's meditation on Ovid from coast to coast,' Entertainment Design 36.4 (April 2002): 28(4).

- ^ abFisher, Philip. The British Theatre Guide. 2003.

- ^Willy Schwarz website, 29 November 2008.

- ^Brantley, Ben. 'Dreams of Metamorphoses Echo in a Larger Space,' New York Times 5 March 2002: E1.

- ^Jefferson, Margo. 'Myth, Magic, and Us Mortals,' New York Times 26 May 2002: A1.

- ^Metamorphoses Internet Broadway Database, Accessed November 26, 2008.

- ^Mckinley, Jesse. 'Ratcheting Up Tony Tension,' New York Times, 15 February 2002

- ^Constellation Theatre’s Aquatic Metamorphoses Runs Deep, Washington City Paper, May 2, 2012. accessed October 21, 2014.

- ^Theatre Review: Metamorphoses at Arena Stage, Washingtonian, February 19, 2013. accessed October 21, 2014. in 2015, Leah Lowe directed a production of the play at Vanderbilt University Theatre with a cast of fifteen student actors.

- ^ abNorthwestern University School of Communication. 2008. Northwestern University. 29 November 2008.

- ^'Mary Zimmerman' at Lookingglass theatre, 30 November 2008

External links[edit]

- Metamorphoses at the Internet Broadway Database

- Metamorphoses at the Internet Broadway Database

Publius Ovidius Naso, known as Ovid, was a prolific Roman poet whose writing influenced Chaucer, Shakespeare, Dante, and Milton. As those men knew, to understand the corpus of Greco-Roman mythology requires familiarity with Ovid's Metamorphoses.

Ovid's Upbringing

Publius Ovidius Naso or Ovid was born on March 20, 43 BCE*, in Sulmo (modern Sulmona, Italy), to an equestrian (moneyed class) family**. His father took him and his one-year-older brother to Rome to study so that they might become public speakers and politicians. Instead of following the career path chosen by his father, Ovid made good use of what he'd learned, but he put his rhetorical education to work in his poetic writing.

Ovid's Metamorphoses

Ovid wrote his Metamorphoses in the epic meter of dactyllic hexameters. It tells stories about the transformations of mostly humans and nymphs into animals, plants, etc. This is very different from the contemporary Roman poet Vergil (Virgil), who used the grand epic meter to showcase the noble history of Rome. Metamorphoses is a storehouse for Greek and Roman mythology.

Ovid as a Source for Roman Social Life

The topics of Ovid's love-based poetry, especially the Amores 'Loves' and Ars Amatoria 'Art of Love,' and his work on the days of the Roman calendar, known as Fasti, give us a look at the social and private lives of ancient Rome in the time of Emperor Augustus. From the perspective of Roman history, Ovid is, therefore, one of the most important of the Roman poets, even though there is debate as to whether he belongs to the Golden or merely the Silver Age of Latin literature.

Ovid as Fluff

John Porter says of Ovid: 'Ovid's poetry is often dismissed as frivolous fluff, and to a large degree it is. But it is very sophisticated fluff and, if read carefully, presents interesting insights into the less serious side of the Augustan Age.'

Carmen et Error and the Resulting Exile

Ovid's plaintive appeals in his writing from exile at Tomi [see § He on the map], on the Black Sea, are less entertaining than his mythological and amatory writing and are also frustrating because, while we know Augustus exiled a 50-year-old Ovid for carmen et error, we don't know exactly what his grave mistake was, so we get an unsolvable puzzle and a writer consumed with self-pity who once was the height of wit, a perfect dinner party guest. Ovid says he saw something he should not have seen. It is assumed that the carmen et error had something to do with Augustus' moral reforms and/or the princeps' promiscuous daughter Julia. [Ovid had acquired the patronage of M. Valerius Messalla Corvinus (64 BCE - CE 8), and become part of the lively social circle around Augustus' daughter Julia.] Augustus banished his granddaughter Julia and Ovid in the same year, CE 8. Ovid's Ars amatoria, a didactic poem purporting to instruct first men and then women on the arts of seduction, is thought to have been the offensive song (Latin: carmen).

Ovid Metamorphoses Mary Innes Pdf Writer Pdf

Technically, since Ovid had not lost his possessions, his relegation to Tomi should not be called 'exile,' but relegatio.

Augustus died while Ovid was in relegation or exile, in CE 14. Unfortunately for the Roman poet, the successor of Augustus, Emperor Tiberius, did not recall Ovid. For Ovid, Rome was the glittering pulse of the world. Being stuck, for whatever reasons, in what is modern Romania led to despair. Ovid died three years after Augustus, at Tomi, and was buried in the area.

Ovid's Writing Chronology

Ovid Metamorphoses Mary Innes Pdf Writer

- Amores (c. 20 BCE)

- Heroides

- Medicamina faciei femineae

- Ars Amatoria (1 BCE)

- Medea

- Remedia Amoris

- Fasti

- Metamorphoses (finished by CE 8)

- Tristia (starting CE 9)

- Epistulae ex Ponto (starting CE 9)

Notes

*Ovid was born a year after the assassination of Julius Caesar and in the same year that Mark Antony was defeated by consuls C. Vibius Pansa and A. Hirtius at Mutina. Ovid lived through the entire reign of Augustus, dying 3 years into Tiberius' reign.

- Roman Empire Timeline

**Ovid's equestrian family had made it to the senatorial ranks since Ovid writes in Tristia iv. 10.29 that he put on the broad stripe of the senatorial class when he donned the manly toga. See: S.G. Owens' Tristia: Book I (1902).

Ovid Metamorphoses Online

References

- Porter, John, Ovid Notes.

- Sean Redmond, Ovid FAQ, Jiffy Comp.